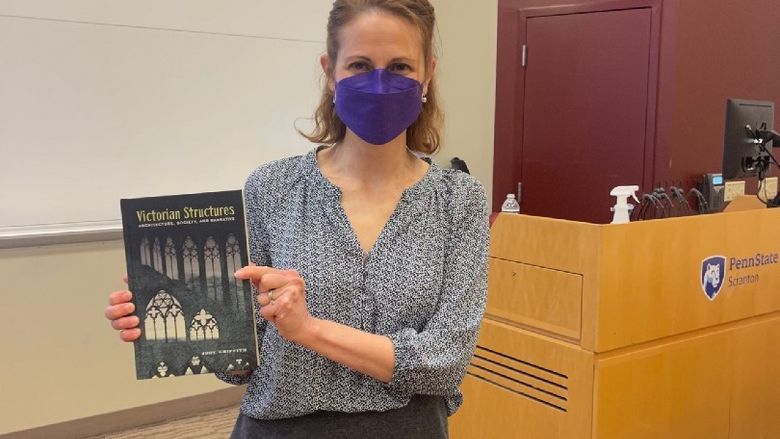

Dr. Jody Griffith, assistant teaching professor in English and composition coordinator at Penn State Scranton, recently finished her first book, "Victorian Structures: Architecture, Society, and Narrative," published by SUNY Press.

Jody Griffith’s favorite author, Thomas Hardy, was an architect before becoming one of the most beloved novelists and poets of the Victorian era.

As it happens, that training served Hardy well as a writer, according to Griffith, assistant teaching professor in English and composition coordinator at Penn State Scranton.

“The more I studied his work, the more I realized that to make sense of his novels, it was important to notice, not just what buildings looked like, but how they functioned in a community, how they changed over time, and how characters moved through them,” she said. “I found that this framework was illuminating for the work of other novelists as well.”

That framework eventually became the guiding principle behind Griffith’s first book of scholarship, “Victorian Structures: Architecture, Society, and Narrative,” which was recently published by SUNY (State University of New York) Press.

In the book, part of SUNY’s "Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century" series, Griffith uses the architectural writings of Victorian critic John Ruskin as the foundation for examining the interaction of physical, social and narrative structures in four Victorian novels – Charles Dickens’ “Little Dorrit,” George Eliot’s “Adam Bede,” and Hardy’s “The Mayor of Casterbridge” and “Jude the Obscure.”

The architectural descriptions in those classic works provide Griffith with a unique and useful way to talk about social and narrative structures -- in other words, she said, “the ways the stories we tell about ourselves create our social structures, and the way our social structures influence the forms those stories take.”

A specialist in Victorian literature, Griffith has long been a fan of the genre’s tendency toward long, intricate stories “overflowing with characters and held together by an intrusive, bossy narrator.”

From a scholarly perspective, she said, it’s an exciting era to study.

While the Victorians tend to be maligned as priggish bores, they happened to live through an especially fascinating period of human history, thanks to industrialization, major social and economic upheaval, numerous scientific breakthroughs and rampant imperialism.

In turn, Griffith noted, the novelists of that era grappled with the best ways to engage with those changes, both thematically and formally.

The book started as Griffith’s doctoral dissertation. She initially settled upon the subject of structures after realizing the evocative descriptions of houses, churches and barns in her favorite Victorian novels weren’t just pleasant filler.

“I think it is thought-provoking that we use a concrete, physical word like ‘structure’ to describe abstract social configurations and narrative arrangements. So, I decided to look at descriptions of physical structures in novels as a parallel for social and narrative structures,” she said. “This architectural lens reveals things about social and narrative structures such as: what gets included and excluded, how structures change over time, and how pieces of old structures get reassembled into new ones.”

For her preliminary research, Griffith turned to the writings of Ruskin, an influential art and social critic in 19th-century England who “didn’t distinguish aesthetic and social values from each other in the ways we might expect,” she said.

In addition to Ruskin’s massive, multi-volume works on painting and architecture, Griffith consulted his architectural treatise, “The Seven Lamps of Architecture,” in which he stakes out specific architectural principles, or “lamps.”

Those principles, she said, allowed her to find thematic and structural connections in various Victorian novels, including those featured in the book.

“I ended up pairing individual lamps with individual novels for each chapter. It provided me with an interesting throughline to follow from one chapter and novel to the next,” said Griffith, noting the cover of her book is based on Ruskin’s architectural sketches in “The Seven Lamps of Architecture.”

Griffith spent several years researching and writing the book. At times, she admitted, it was a bit of a slog.

“I always commiserate with my students — I think writing is hard! That blank screen! I generally avoid it as long as possible,” she said. “But it also can be satisfying to figure out new ideas and make new connections. I also enjoy the revision process, because it’s kind of like solving a puzzle. That’s a good thing, as this book required a lot of revision!”

Meanwhile, SUNY Press proved to be a great collaborator, offering helpful guidance, encouragement and professionalism through every stage of the production process, she said.

Overall, she’s very happy with the final product.

“It’s pretty cool to see it finished in book form,” Griffith said. “I think there are some really interesting conversations happening now in literary scholarship about form and structure, so I hope I may contribute to that in a small way.”

For more information on Griffith’s book, visit: www.sunypress.edu/p-6872-victorian-structures.aspx.