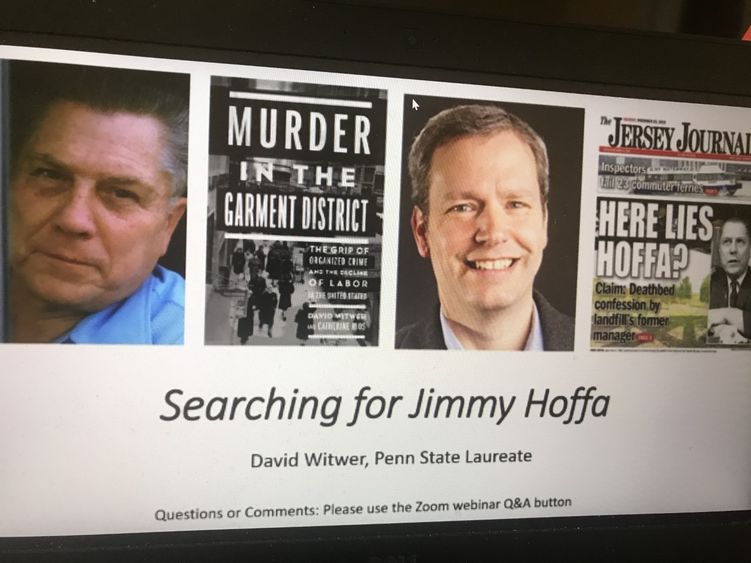

Penn State Laureate David Witwer discussed the disappearance and legacy of Teamsters leader Jimmy Hoffa during his March 3 lecture for the campus community.

DUNMORE, Pa. – Teamsters leader James R. Hoffa vanished 46 years ago, but the effects his disappearance had on the organized labor movement continue to linger today.

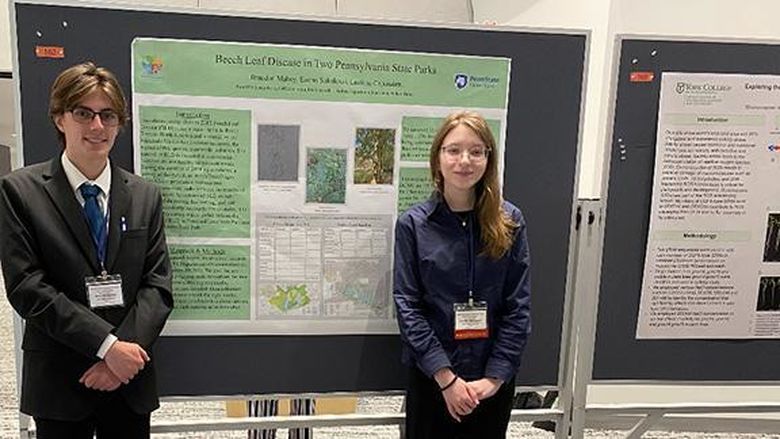

That was among the takeaways from Penn State Laureate David Witwer’s fascinating lecture, “Searching for Jimmy Hoffa: The Disappearance of America’s Most Notorious Labor Leader and Why It Still Matters Today,” which he presented virtually to the Penn State Scranton campus community on Wednesday, March 3.

“I really appreciate the chance to talk to you all today,” said Witwer, professor of American studies in Penn State Harrisburg’s School of Humanities.

Since being named laureate for the 2020-21 academic year, Witwer has been giving a series of Zoom talks drawing on his scholarly expertise in corruption, organized crime and labor racketeering. Established in 2008, the Penn State Laureate is a full-time faculty member in the arts or humanities who is assigned half-time for one academic year to bring greater visibility to the arts, humanities and the University, as well as their own work, through appearances across the commonwealth.

Witwer’s lecture focused on Hoffa as a singular American figure who symbolized the far-reaching power of the 20th-century organized labor movement, as well as the corruption spawned by the movement’s transactional relationship with organized crime.

While Hoffa’s 1975 disappearance and likely murder at the hands of the mob continue to fascinate the public, his celebrity status as the head of a labor union might be hard to fathom for those who weren’t around to see it firsthand, said Witwer. For contextual purposes, he asked the audience to picture a contemporary public figure like NFL quarterback Tom Brady suddenly going missing today.

“Imagine the amount of attention that would attract. That’s what it was like when Hoffa disappeared,” said Witwer, noting Hoffa’s charisma and pugnaciousness inspired both deep admiration from working-class union members and relentless antagonism from government officials like Robert F. Kennedy.

Before entering academia, Witwer worked for the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office and New York State Organized Crime Task Force. During that period, he spent hours listening to telephone conversations between corrupt union leaders and organized crime figures.

“So, when I write about these topics now, I write about them as someone who has seen the gritty details,” Witwer said.

Witwer’s presentation combined elements of his current Hoffa-centered book project with his previous book, “Murder in the Garment District: The Grip of Organized Crime and the Decline of Labor in the United States.” The latter book, co-authored with Catherine Rios, associate professor of communications and humanities at Penn State Harrisburg, explores the union-mafia relationship through the lens of the 1949 murder of union organizer William Lurye in New York City.

Essentially, that corrupt relationship was one of necessity for the labor movement. In order for unions to achieve their high-minded goals for their blue-collar constituency, they had to engage in a pragmatic partnership with the deeply entrenched organized crime figures who controlled entire industries through violence and bribery.

“For the unions, the only way to move forward was to make some sort of accommodation with organized crime,” Witwer said. “It’s not some otherworldly system, but one very much like our own, only with different rules.”

The Scranton/Wilkes-Barre area itself was a hotbed of union-mob activity. Here, International Ladies Garment Workers Union organizer Min Matheson had to “make the best deal she could” when organizing workers from the Pittston garment factories controlled by Kingston mob boss Russell Bufalino, Witwer said.

Hoffa understood this corrupt bargain very well, and his relationship with Bufalino was documented in Charles Brandt’s 2004 book, “I Heard You Paint Houses,” which served as the basis for director Martin Scorsese’s 2019 film, “The Irishman,” starring Al Pacino as Hoffa, Joe Pesci as Bufalino and Robert DeNiro as Philadelphia Teamsters official Frank Sheerin.

An associate of both Bufalino and Hoffa, Sheerin told Brandt that he killed Hoffa on mob orders. It’s a claim Witwer finds dubious.

“Color me skeptical of Frank Sheerin,” he said, noting Sheerin was a notorious liar and was not known to be a prolific mafia hitman.

One thing Witwer knows for sure is that Hoffa’s disappearance had monumental consequences. For organized crime, it led to an extremely successful crackdown by the FBI and the Justice Department. For organized labor, it resulted in widespread anti-labor sentiment and policies that continue to this day.

For more information on Witwer, visit: https://harrisburg.psu.edu/faculty-and-staff/david-witwer-phd.